Fragments of a Forgotten Matriarch

“If you want to understand any woman, you must first ask about her mother and then listen carefully.”

—Anita Diamant, The Red Tent

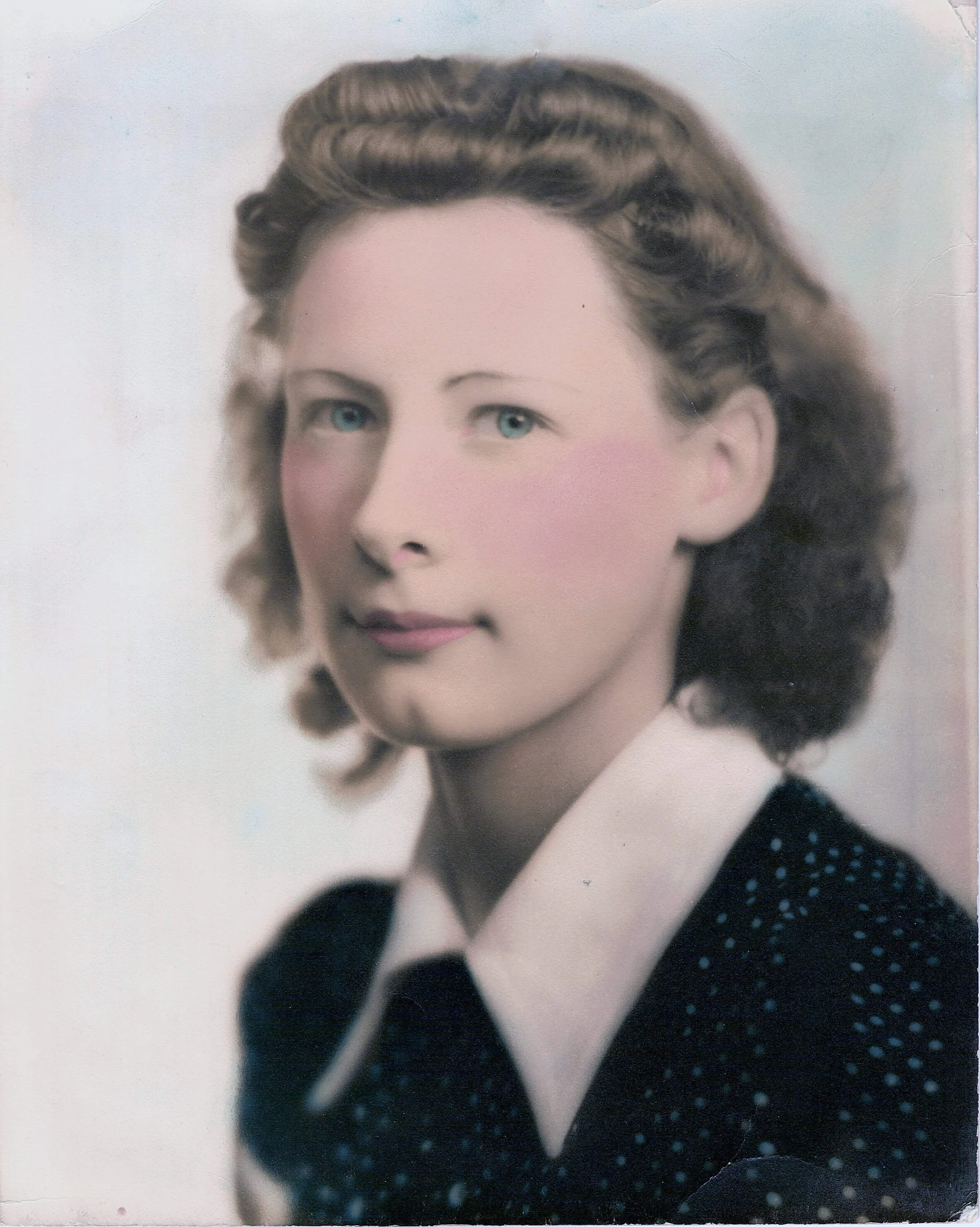

Although my mother’s mother was alive for the first 15 years of my life, I never really knew her. She must have been lucid when I was born, cradling me in her arms, wiping the spit-up from my mouth, and kissing my forehead. She must have whispered soft words, her nose nuzzled against mine—the same nose I’d grow to inherit.

But I don’t have those memories inside me.

Growing up, my brothers and I took turns pushing her in her wheelchair through the zoo and down the boardwalk. We’d race, our hands gripping the cool metal handles as we veered through flocks of seagulls, laughing at her sharp cries. We spun her in dizzying circles, pulled wheelies into elevators, and matched her squeals with our own. When my mom returned to reclaim control, we’d scatter into the chaos of childhood, unburdened by the weight of care.

On special visits, my mother and I would tuck my grandmother into a worn red booth at Marie Callender’s. Her blue eyes sparkled, even as my mom spooned bites of chicken-pot-pie into her mouth. I’d watch as she dabbed the corners of my grandmother’s papery lips with a lace handkerchief, a ritual of tenderness. The coconut cream pie would arrive, the only time dessert was allowed in restaurants, and I’d scrape the last bit of whipped cream from the plate. But each time, her voice would break through the moment, fretful and repeating: “Where’s my purse? Where’s my purse?” Her bony fingers clutched the bag tightly to her chest, convinced it had been stolen.

My mom, unwavering, would soothe her, over and over, while blurry faces from nearby tables glanced our way, their middle-class meals interrupted by our drama. I’d stare at the floor, ashamed of their eyes on us, the weight of their curiosity heavier than any plate of pie.

…

There’s one phrase my grandmother repeated like a mantra, its rhythm still pulsing in my ribs when I close my eyes. "Mm, take it, take it." I didn’t understand the words then, their quiet insistence, but they became a constant hum whenever we visited.

It wasn’t until the end—when only my mother and I could bear the visits to the home—that I heard the full phrase.

“I can’t take it.”

Her voice trembled, a small crack in the foundation of my world. A plea, fragile and raw, hanging in the air between us.

At some point, my grandmother began calling me by my mother’s name. She no longer recognized her own daughter, but she knew me. That was around the time she had to move into the home, a place I dreaded. The boys couldn’t handle it, so they’d drop off my mother and me, disappearing for two hours of freedom while we stayed behind. I envied their escape. They sipped milkshakes while I sat, suffocating in the smell of too-sweet prunes and the medicinal air that clung to skin.

“Go away!” Grandma would shout at my mother as she attempted to brush her thinning hair or paint her nails with pink polish. “I want to be with my daughter now.”

She’d take my hand and rock a baby doll to sleep, her fingers tracing over the doll’s eyelashes with delicate care. She no longer whispered her mantra, but she hummed it, mechanically, until her eyes closed and her glasses slipped down her nose. We’d swaddle her in bed, sit in silence, and wait for the boys to come back. I pinched the skin on the inside of my wrist, creating little white crescent moons, small pockets of pain that offered me a strange relief from the emotional weight pressing on my chest.

…

One night, my mother stood up abruptly in the middle of dinner. Her fork clattered against her plate.

“I have to go,” she whispered, the urgency clear in her voice.

She left her plate of spaghetti half-eaten and began the six-hour drive up north to the place she came from. She made it just in time to hold her mother’s hands in her own, the two of them locked together for the final ten minutes. I knew my grandmother had passed before the boys did. I’d been sitting by the phone, long after the spaghetti had gone cold, waiting for the call that I knew was coming.

I don’t remember the funeral or the bitter squabble over the wedding ring. But I do remember her eyes—my eyes. Her hands—my hands. The phrase that haunted me: I can’t take it. A baby doll cradled in the crooked arms of a woman who was anxious and afraid, but not alone. A high school yearbook tucked into the corner of the room, pages yellowed with secrets of a lover lost to war. A younger man. A baby born eight months after the wedding.

…

My mother never knew how old her mother was until the death certificate was signed. There were so many stories—stories locked away inside my grandmother, now buried in the sea of her fading mind. It wasn’t until years later, when I was a grown woman myself, that I began to wonder who my grandmother had really been before the disease took her. Before my grandfather. Before the children. Before me.

We teased my mother when she started slipping into the same panicked searches—her voice strained as she rummaged through her purse, the one resting squarely on her hip, convinced it was lost. I’d roll my eyes and sigh, frustrated by her inability to control her anxiety in public, embarrassed by the wide-eyed stares we drew in restaurants. I didn’t want to see the reflection of my grandmother in her—the impatience, the trembling hands.

…

They say we turn into our mothers as we grow older. My mother’s relationship with her own mother was tangled with secrets and silence. My relationship with my mother was filled with slammed doors, crossed arms, and a stubborn refusal to speak the truth. As teenagers, when my brothers teased me about becoming my mother or my grandmother, I’d swat them away. I vowed I’d never become like them. I was sure I’d be strong enough to protect my mind, to safeguard my dignity from the public displays of fear and worry.

If we’re lucky. life pulls us out of our pride. It reminds us, again and again, that we are not truly in control. Nature is stronger than our human intentions, and I’ve been nurtured by the DNA of the women who raised me.

I can feel it happening now—the same fear, the same anxiety wrapping itself around my lungs, tightening its grip with every passing year. It’s subtle at first, creeping in during moments of stillness. Then, during the attacks, you lose sight of everything—the shapes of the objects around you blur, the weight of the bag in your hand becomes unbearable. Even the voices of loved ones saying “It’s alright, we’re right here” become distant and untrustworthy.

I’m afraid of what will happen if my mother becomes her mother. I’m afraid of becoming my mother. What stories will slip through the cracks, untold? What pieces of my life will drift away, discarded and insignificant? What connections link the three of us, beyond this shared worry, this anxiety that seems to pass from one generation to the next?

The cycle of mothers and daughters is filled with words we’ve been too stubborn to say—stories that haven’t been shared, wisdom that feels just out of reach. And as I sit here, tracing the lines that connect us, I wonder if it’s too late now to begin talking about the truth.